In 87% of the 17,000+ classrooms visited, students were tasked with low-level thinking activities. Antonetti and Garver identified four reasons that the abundance of learning was occurring at this level.

- Teacher focused classrooms. Students passively receive information which they later repeat, reproduce or restate.

- Professional development not focused on better instructional design or presentation styles and pedagogy that supports active learning.

- Standardized assessments encourage educators to use rote instruction for students to have success in low-level tasks.

- Students cling to being "right and done".

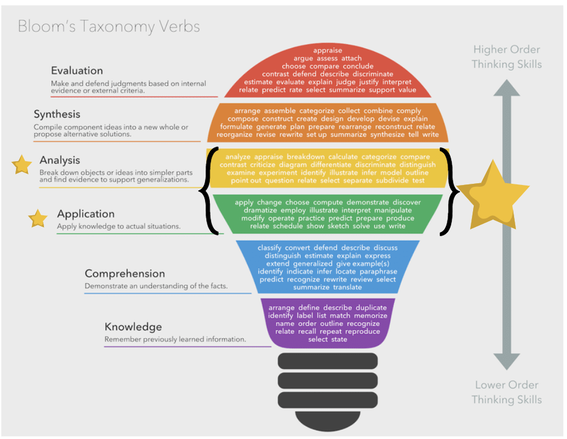

How do we move the needle and get better in 87% of these classrooms? It's simple; we learn! As educators, we have to evolve in our practices and improve instructional design and incorporate advances in brain science into learning experiences. In the 17,000+ classroom visits, they found that the key to raising thinking in a meaningful way was to focus on the middle two levels of Bloom's taxonomy, application, and analysis.

- Application - the human brain likes to gather information and then find ways to use it.

- Analysis - finding patterns is one of the most natural ways for our brains to learn.

I often hear focus on "the verb" to increase the level of thinking, but Antonetti and Garver point us towards looking at our Instructional design and what science tells us about how the brain learns. As a student, when asked a question by a teacher, I would give an answer if I knew it. If not, I'd more than likely sit and wait for the next person to provide the solution. If the teacher is in control of all of the questions, what impact does that have on learning?

"We have seen this phenomenon repeated in classrooms in which the thinking is pushed to the middle. students who are working through their own content patterns -yet do not have all of the answers- will voluntarily go and seek more information." Antonetti and Garver

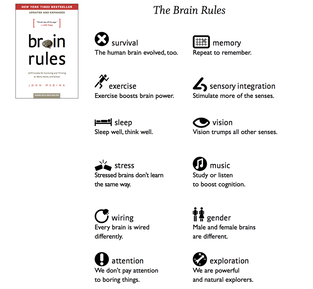

So if this is how our brains are wired, how can instructional design help facilitate students towards engaging in learning that involves application and analyses? John Medina, a molecular biologist, published Brain Rules in 2008. His researched formed 12 big ideas about the brain that apply to our daily lives, especially at work and school. (It's been 11 years since his rules were published and I have never read his work.) The complete list of Brain Rules can be accessed here and here.

Brain Rules Introduction from Pear Press on Vimeo.

In the podcast Vrain Waves hosts Ben and Becky interview John Medina. Medina connects his research to both learning and teachers. (If you don't have time now to listen to the podcast, I highly encourage you to stop and add it to your playlist. It is SO good!)

- The students were shown a group of images. (Brain Rule #10- Vision)

- The teacher partnered students up and assigned roles. One student was to be the recorder and one was to be the reporter. Students were given 30 seconds to find as many patterns as they could in the three pictures. (Brain rule #4 - Attention)

- At the end of 30 seconds, the teacher had pairs share out. Some of the patterns shared by students were; there all big things, there all things people didn't make, you usually find all of these things outside, they are all rough, etc. The students continued to share out until they exhausted the patterns that they had found. (Mid-level thinking here. Students are analyzing)

- The teacher asked if every group had found the pattern of size, and they had. Next, she had students switch roles in their pairs and then gave them 30 seconds to think of as many words as they could think of that mean "big".

- After 30 seconds students shared out more than 20 synonyms before the teacher heard the vocabulary word she wanted students to learn. That word was MASSIVE. When she heard it she identified it as a "cool word" and added it to the vocabulary list for the week. No need for students to be given a definition to memorize, they had told her what it meant.

These ideas and resources are just the tip of the iceberg of ways we can improve the experiences students are having in classrooms and teachers are having in their professional learning. The next time you plan instruction, how might you help activate learning by what science has taught us about the brain? How might learners experience and process the content in a more meaningful way using application and analysis?

Next up on my blog, I'll look into the levels of engagement in learning. Are there qualities present in instruction that increase student engagement?

RSS Feed

RSS Feed